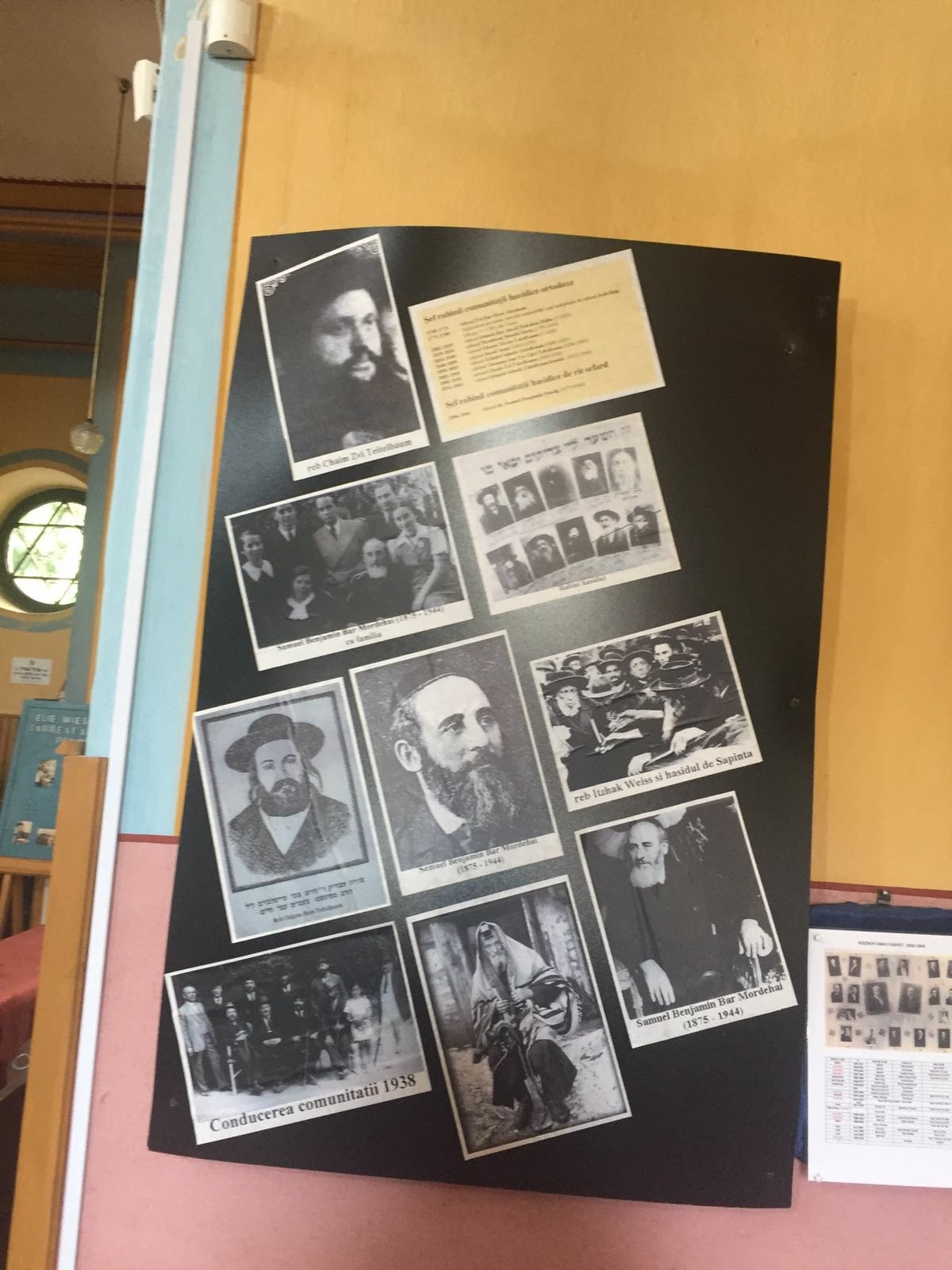

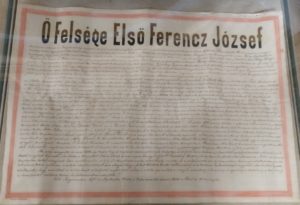

In the 19th century, Hungarian jewry developed its very own brand of Reform movement: The Neolog denominaton. It deviates from the typical Reform ideas at least insofar as women are not seated with the men; but it shares its rejection of the Talmud; i.e. basically the oral Thora and the teachings of generations upon generations of rabbis. As stated in a document that was found during the renovation of Oradea’s Neolog synagogue,

“… to serve as as place of worship for the city’s Jews so that within its walls pure religiosity and progressive ideas be preached, along with moral tenets cleansed of sophistry, Hungarian national spirit and patriotic devotion, equality and fraternity, loyalty to the King and love for the country forever and ever!!! [sic] Written in Oradea on 24th September 1878 …

As one can see, neologism advocates patriotism towards Hungary very much in the same way that German reformers sought to display “true” German patriotism. The motive was clear in both cases: The newly “emancipated” jews hoped for recognition as real Germans and Hungarians, respectively.

I am not going to poke fun at them for choosing a path that led nowhere. It is not my place. In hindsight we all are wiser. Nor do I need to point out that this sort of patriotic enthusiasm turned out to be but a pipe dream that was followed by a cruel awakening.

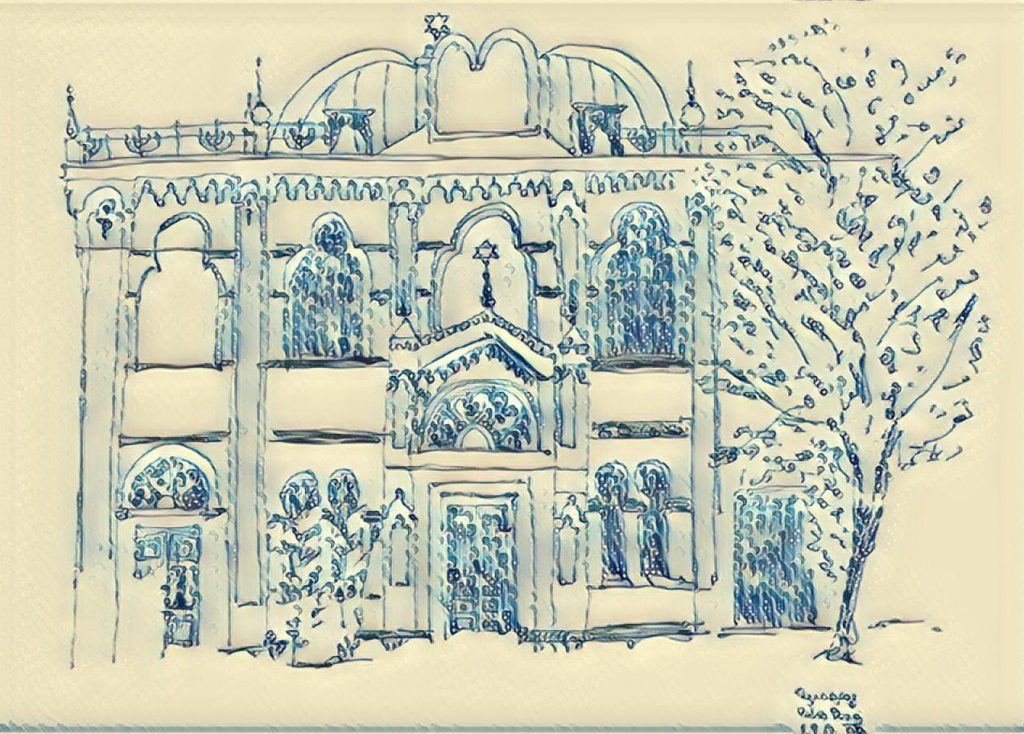

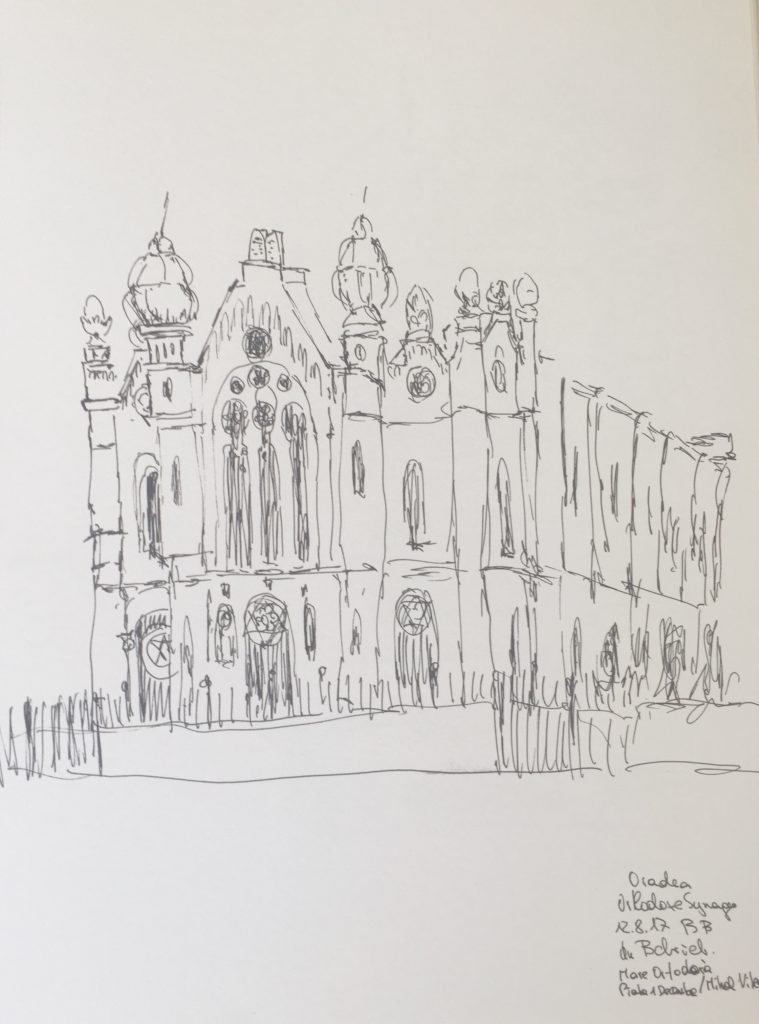

Instead, I would like to share with you the astounding beauty of this building in the center of Oradea, right by the river Crișul Repede.

You may find of interest a few oddities of Neolog architecture; i.e. there is no bimah with a shulchan to read the Torah (this is done all the way in front). This way, the seating arrangements resemble church benches. Furthermore, there is an organ up above the aron koidesh. Neologism obviously has no problem with music on Shabbes.

After nearly two weeks in northern Romania we are heading back west, towards home. And we have chosen the beautiful city of Oradea as the end of our journey. Here we spend our second and last Shabbes in Romania.

After nearly two weeks in northern Romania we are heading back west, towards home. And we have chosen the beautiful city of Oradea as the end of our journey. Here we spend our second and last Shabbes in Romania. Well, actually not.

Well, actually not.

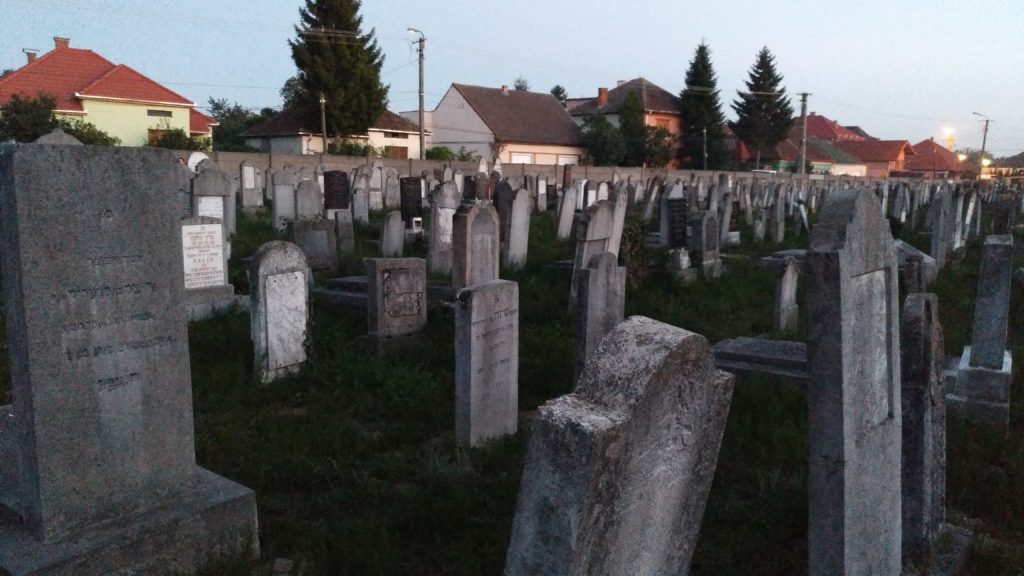

We are searching for my great-grandmother’s grave; Pessie Rennert, née Katz. Though she lived in the nearby village of Putna she was buried here. There is no jewish cemetery in Putna.

We are searching for my great-grandmother’s grave; Pessie Rennert, née Katz. Though she lived in the nearby village of Putna she was buried here. There is no jewish cemetery in Putna.